It’s been more than a month since I last posted and while I have been very busy at home, not keeping up with posts has been dragging on me.

I have been focused on stuff around the house and lamenting that I will not be aboard Pandora this winter, something that with rare exception, has not happened for more than a decade.

To that point, it was just a few degrees above freezing when I got up this morning. And, it’s only going to get worse.

After the unfortunate experience with orcas near Gibraltar, I have been wondering what I might have done differently to avoid the damage. In the event that you missed that, check out this post that I did shortly after the “attack” that took part of my rudder and badly damaged my Hydrovane auxiliary steering.

Some skippers do a massive amount of research when they are heading somewhere new but I tend to be a bit more cusary than some even though I talk to “those who have gone before” with an eye toward getting a feel for what lies ahead.

Such was the case with my hope to pass through “orca alley” near the Iberian peninsula as I made my way the final distance to Gibraltar.

Not to repeat too much from that earlier post I noted above, but during our last night before reaching Gibraltar, our next landfall, Pandora had handled some rough weather overnight, gusts on the beam in the mid-30s and big seas that broke over the deck several times. By morning, the worst had eased, and soon the coast of Morocco was just visible off the starboard bow.

I guess that being past the rough conditions of the prior night kept me from focusing fully on the possibility of being “whacked” as we got near Gibraltar. Additionally, as is my custom, we were then close enough to shore to activate Starlink without racking up extra offshore costs, so I turned it on.

Unfortunately, this distracted us from keeping a careful lookout which I do think had a bearing on the orcas pod being able to approach us without us even noticing.

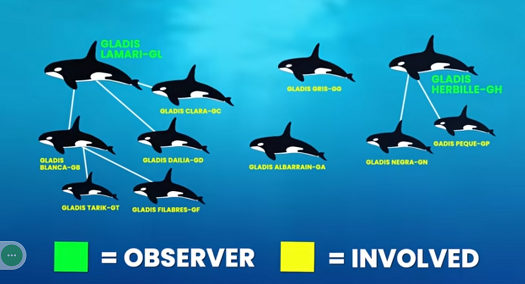

For months I had been following reports of orca attacks on sailboats along the Iberian coast—rudders broken clean off, stainless rudder posts bent and a few boats sunk. The Strait of Gibraltar has been the epicenter of this behavior since it began around 2020. There are a dozen or so individuals, mostly juveniles, believed to be involved. Scientists think they are “practicing” hunting or simply playing, attacking rudders for sport. In keeping with our habit of giving notable animals names, Iberian orca that have been involved in the attacks with vessels are referred to as Gladis.

As I mentioned in many posts prior to my final leg from Sao Miguel in the Azores, I had done my homework. I studied www.orcas.pt, a comprehensive site that tracks orca sightings and attacks, and planned a route that seemed the least risky. The data showed very few recent encounters along the Moroccan coast, compared with many farther north where the orcas had followed the tuna. I figured we would slip through safely on that southern track.

We were within a few miles of the narrowest part of the strait of Gibraltar, making about ten and a half knots over the ground, with a push from the current, when it happened. The boat shuddered violently, the wheel spun out of my hands, Pandora lurching to one side, and again, and again…

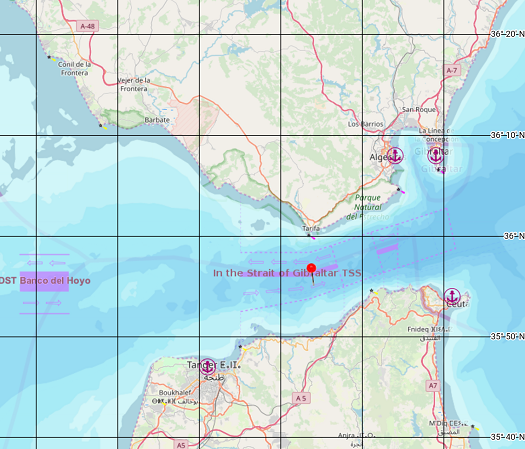

This shot shows more or less, where the attack happened. As I was so close to Gibraltar I thought that the worse was behind me. Oops…

For a few seconds, none of us knew what had happened. Had we hit something? Then a massive black-and-white shape slid beneath the stern. An orca. And then another. And another. In total, maybe four or five of them, each easily fifteen to twenty feet long, closing around us, taking turns striking the rudder.

I have been told that orcas don’t actually bite the rudder they ram it from the side. This image, not taken by me, shows the relative size of these creatures to the rudder itself. As you can imagine, rudder vs 10 ton orcas, the outcome is pretty clear.

One of my crew grabbed his phone and started filming. The footage is grainy, but it captures the chaos—the sudden jerks of the wheel, the froth behind us, the unmistakable fin slicing past the transom. All I could think was “will Pandora sink?.” (You can watch the short clip [here].)

It is hard to describe what that moment felt like—equal parts awe and terror. These are magnificent animals, but knowing that one well-placed hit could snap the rudder post or crack the hull was sobering.

A few weeks ago I presented about our trip to the Azores as well as the “attack” at a yacht club on The Cape. And as luck would have it, that morning there was a segment about a sinking on the Today Show.

In this case, the video was taken from a nearby boat as the sailboat was repeatedly rammed and ultimately sunk.

While the damage to Pandora was minor compared to a sinking, I clearly felt Pandora’s stern being roughly pushed from side to side as is shown in the video. It was a very unpleasant feeling.

I have wondered what leads to some boats sinking and others just suffering a damaged rudder. Was it something about the rudder, the strength of the hull, rudder bearings or the way that the rudder was constructed that made a difference?

Pandora was designed and constructed as a solid, if modern, offshore boat and as an added feature of strength, the entire hull incorporates a layer of Kevlar, which is pretty tough stuff.

As part of that “toughness” the rudder post is carbon fiber. A feature of carbon fiber is that it does not bend. In a hit like that, it either holds or it shatters dramatically. In this case, it held.

As the orcas battered the rudder the bottom third broke off, leaving it hanging by a flap of fiberglass. Later, I learned that this was a blessing in disguise: my rudder was built with a sacrificial lower section, meant to shear away cleanly in a grounding—or, apparently, an orca encounter. I have heard that once the damage is done, a portion of the rudder snapped off, that they often loose interest but keep pounding on rudders that resist their efforts, leading to more substantial damage.

Interestingly, years ago I hit my SAGA 43 rudder HARD on a rock and while the stainless shank bent, the bottom of the rudder did not break. In asking a friend who is very familiar with production boat construction about my experience with the orcas and the broken rudder and he told me that most production boats have a stainless post that goes all the way to the bottom of the rudder. This would not be good in an orcas strike as the rudder itself would likely hold, perhaps frustrating the orcas which would encourage them to continue striking the rudder until something let go. It is likely that the shaft would bend and the longer that the strikes continued, the worse the potential damage would be.

Yachts with stainless rudder posts often end up with bent shafts that jam their rudder against the hull and perhaps linkages destroyed, leaving them without steering entirely. Once the orcas get started they tend to keep hammering until something gives.

In some cases where boats sunk, it was because the lower support for the rudder post broke away from the hull, leaving a large hole around the then-destroyed lower bearing and hull. With a large hole like that it doesn’t take long to for the boat to sink.

Our Hydrovane, wind vane steering, did not escape either—the reinforced plastic rudder was cracked and bent 90 degrees. Fortunately, there was enough of our primary rudder left so I could still steer, if sluggishly, so we limped on toward Gibraltar at reduced speed, dragging the remnants of both rudders through the water, substantially cutting our speed.

I keep the Hydrovane in place in the event of a steering problem and so wish that I had just pulled the plastic rudder when things calmed down as we approached the coast. Now damaged, the repairs needed are fairly substantial. Lessons learned…

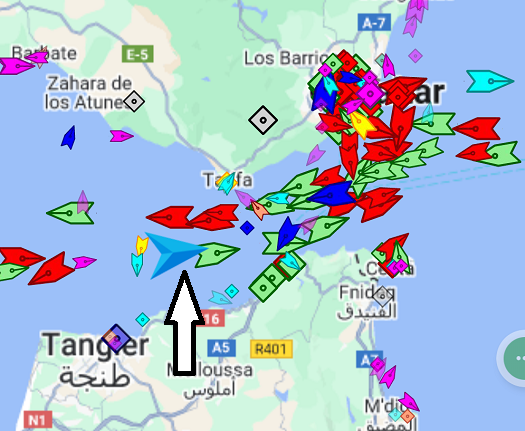

Shaken and really ready to be in port, I was on the southern side of the Gibraltar shipping channel. I found crossing the busy channel to be more than a bit nerve wracking as I threaded my way behind ships with the hope of getting out of harm’s way before the next ship came up on me. This shows just how busy it was. Note the arrow I have placed on the image which is where we were shortly after the attack.

We tied up at the marina in Gibraltar just before sunset, grateful to be in port. The next morning I put on a wetsuit, hooked up my hookah dive compressor, and went over the side with a handsaw to finish removing the remains of the primary and Hydrovane rudders. The section of the primary rudder that had snapped remained attached by its fiberglass skin, which turned out to be fortunate as the yard in Almerimar, Spain was able tore-bond the damaged section once we hauled out.

Lessons from the Attack

Looking back, there is a lot I might have done differently had I known then what I know now. The first and most obvious lesson is that while I thought the orcas were farther north they were waiting right where we made landfall. There have been many fewer attacks in shallow water, under 20m so I should have hugged the coastline but due to crew departure plans and my desire to make port, I didn’t take the “slower” coastal route.

The orcas.pt site is an excellent tool for sailors crossing this coast. It offers an interactive map of sightings and attacks, depth data, and Telegram groups where cruisers share real-time positions. Before transiting the Gibraltar or Portuguese zones, it is worth checking the latest sightings and attacks and adjusting your track. Data from hundreds of sailors show that most interactions happen in water 20 to 1000 meters deep, where the orcas hunt bluefin tuna. Inside 20 meters, encounters are less common. Where I was when attacked I was only about 3-4 miles from shallow “safe” depth, so perhaps had we kept a better lookout we might have been able to head to shore when they were approaching.

To that point, the advice is to hug the 20-meter contour—in water shallow enough that the orcas do not typically frequent those areas. Safety is not guaranteed, but statistically it reduces risk.

So, what do you do if you see orcas?

- Disengage the autopilot so the wheel can spin freely.

- Keep hands loosely on the helm—a hit can whip the wheel dangerously.

- Power toward shallower water as quickly as possible.

- Do not use fireworks, or noise-makers—they are illegal in Spanish and Portuguese waters and may aggravate the whales.

- Document and report your encounter to Orcas.pt and local maritime authorities. Every report improves the database for future sailors.

- Remove auxiliary wind steering rudder as any attacks are likely to take out that too. If needed, it can be put back in place.

- There has been some preliminary reports that towing certain acoustic devices may deter some attacks but these devices have not undergone formal testing.

Well, hindsight is 20-20 and while advice is changing, this is the playbook today. A few years ago, sailors were told to stop engines and drift, but research now suggests that quiet, stationary boats may encourage more prolonged interaction. Better to keep moving, steadily, toward safety.

From Gibraltar, I motor-sailed east to Almerimar, Spain, about 150 miles, where she was hauled for the season. The yard there was able to repair the rudder and Pandora is as good as new once again.

Here is what her rudder looked like when she was hauled on Almerimar.

Now, as good as new…

For sailors used to worrying about weather and gear failure, the idea of being attacked by whales, actually the largest member of the dolphin family, feels almost absurd. But for now, it is part of the calculus of cruising these waters. The reports continue: dozens of boats attacked each season, mostly between May and October, as the orcas follow the tuna migration north and south.

Would I do it again?

Yes—but I would plan differently. Instead of being concerned about making landfall in Gibraltar on a particular day, I would hug the shore and be less concerned about keeping a schedule to satisfy crew plans.

There is still a lot we do not understand about why these orcas are doing what they do but the prevailing theory is that they are just out for a good time. But to be on the receiving end still seems more like an attack than fun.

Brenda likes an analogy comparing all this to a cat “playing” with a mouse. The cat is clearly enjoying themselves while the mouse is terrified. Ultimately, the mouse looses, is killed and eaten. Sure, it’s fun for the orcas but to be on the receiving end, not so great.

One thing for sure that as an apex predator with an abundant food supply, they have plenty of time on their hands to pursue “hobbies” and hopefully they will decide that there is something even more fun than damaging cruising boats.

In the end, I count myself lucky. Pandora did not sink, the crew came through unscathed, and I have a great story to talk about, again and again.

And, speaking of “telling the story”, I have been invited to give a number of talks on the subject, the first of which will be an interview style with Rui, the founder of orcas.pt. He and I will talk about this issue and provide some thoughts on “best practices” on December 9th at 5:00pm. If you re curious and would like to participate in the webinar, follow this link to the Salty Dawg webinar site to learn more.

Broken rudder and bruised pride aside, the run to Spain was memorable. And, with cruising the Med for the next few seasons, Brenda and I are looking forward to this next chapter, hopefully somewhere with fewer “playful” whales.

And under the category of “I wish I knew then, what I know now”. Well, actually I knew enough but didn’t follow the basic rule of “don’t try to keep to a schedule”. I was very focused on getting to port and had I just taken a bit longer and hugged the coast, I probably (PERHAPS?) could have avoided the attack.

However, as was once said, “experience is what you get when you don’t get what you want”. And in this case, I now have a great story to tell.

And tell it I will. Again and Again…