Anyone who spends time on the water—especially offshore—knows that the ocean can be unforgiving.

What complicates that reality today is the expectation created by modern technology. Starlink, instantaneous communication, and powerful weather tools like PredictWind can foster a subtle but dangerous illusion: that knowing more automatically means being safer. That’s only partially true.

As rally director for the Salty Dawg Sailing Association, I often heard comments suggesting that sailing in a rally meant help was close at hand. While excellent communication and shoreside support are valuable, they don’t change the fundamentals nearly as much as many believe.

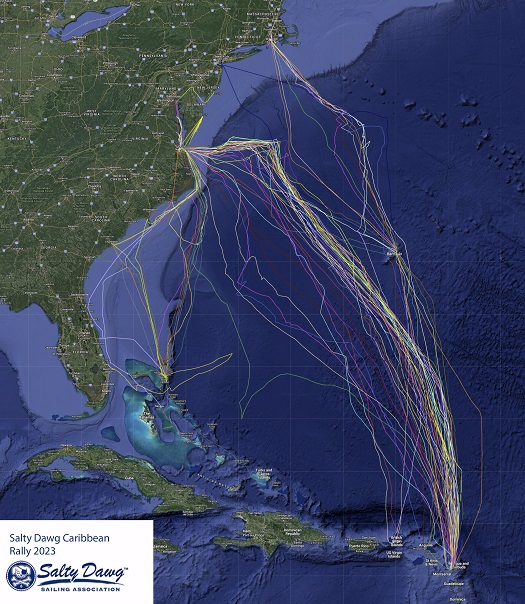

Casual dockside conversations—especially with those who haven’t spent time offshore—often include some version of, “Well, it must be safer having others around in a rally.” They’re usually surprised when I explain that during an offshore passage we almost never see another rally boat, even when a hundred boats are out there together.

The tracking map reinforces the illusion. Watching dots crawl across the screen gives the impression that everyone is close. They aren’t.

The simple fact is that once you’re offshore, you’re subject to the same perils mariners have faced for centuries—albeit with better odds of a good outcome. You are essentially on your own. The real advantage of modern weather tools is not safety in the moment, but avoidance: the ability to steer clear of truly dangerous conditions, or at least receive enough warning to prepare when challenging weather is unavoidable.

Someone once told me, “A real sailor should be prepared for whatever they encounter. If they aren’t, they shouldn’t be out there. And if you’re prepared, just go—weather or not.” With the tools available today, leaving without the best possible information is not bold—it’s irresponsible, and it puts others at risk.

Most passages last a week or two. With good forecasting—both before departure and underway—it’s generally reasonable to avoid most conditions that would otherwise test the limits of boat and crew.

Good information, however, is only part of the equation. A successful voyage ultimately depends on the condition of the boat, the quality of preparation, and the conditions encountered along the way.

And just as important as all of that is attitude.

For many sailors, the Fisherman’s Prayer speaks directly to this point. The classic poem by Winfred Ernest Garrison goes like this:

Thy sea, O God, so great,

My boat so small.

It cannot be that any happy fate

Will me befall

Save as Thy goodness opens paths for me

Through the consuming vastness of the sea.Thy winds, O God, so strong,

So slight my sail.

How could I curb and bit them on the long

And saltry trail,

Unless Thy love were mightier than the wrath

Of all the tempests that beset my path?Thy world, O God, so fierce,

And I so frail.

Yet, though its arrows threaten oft to pierce

My fragile mail,

Cities of refuge rise where dangers cease,

Sweet silences abound, and all is peace.

Though not explicitly about sailing, Garrison’s words speak directly to our relationship with the sea.

Garrison was born in St. Louis in 1879, which surprised me. I had always assumed the poem was centuries old. More surprising still: he had never been to sea. And yet he captured, perfectly, the universal thoughts of anyone who has found themselves hundreds—or thousands—of miles from land in a small boat.

What technology cannot provide is nerve, patience, and judgment. It is attitude—every bit as much as electronics—that gives us our best chance of a good outcome.

Strip away shoreside support, Starlink, and the most current forecasts, and the truth remains: offshore, you take what you’re given and deal with it as calmly and deliberately as possible.

There’s an old adage: “If you feel like you should reef, you should have done so already.”

Last summer, on my approach to the coast of Portugal—the final night of a passage from São Miguel to Gibraltar—the GRIBs suggested 20–25 knots on the beam. What I found in the middle of the night was closer to 30–35. A big difference.

I was double-reefed with a partially rolled jib, but I should have put in the third reef. Once things were fully “on,” with waves occasionally breaking over the cabin top, I couldn’t bring myself to go forward to secure the clew. We did fine, but the boat was clearly overpowered.

I mention this because while I’ve used Chris Parker for weather routing throughout our cruising life, on that passage I only requested forecasts for the first few days. I assumed I could handle the rest unless something changed.

What I didn’t know—and learned later from Chris—is that models routinely underestimate winds immediately east of Portugal. I simply wasn’t as prepared as I should have been.

I strongly believe in using professional weather routing for the entire passage. In this case, I went against my own advice. We were lucky. Pandora came through without damage, and while it was tough at times, we were never in real danger. Still, luck played a role—and next time, on a 900-mile run, I won’t skimp on support.

Support or not, the truth remains:

Thy sea so great. My boat so small.

When acquaintances learn that we have a boat, one of the first questions is always, “How big is it?” My answer is, “That depends on how close you are to a dock.”

Pandora feels enormous when I’m inches from something hard. Hundreds of miles offshore, she feels very small indeed.

Those words—“Thy sea so great and my boat so small”—have been proven to me more than once.

I believe strongly that it is the skipper’s responsibility to use every available resource, even while accepting that offshore we ultimately rely on ourselves. One area that concerns me is what I think of as amateur weather routing—skippers who believe models alone are enough.

After more than a decade and over 30,000 bluewater miles, I’ve learned repeatedly that unless weather is your full-time focus, you simply can’t match the knowledge of someone who has spent years refining that craft.

A well-found boat, modern equipment, and weather support are only as good as the skipper and crew. To believe otherwise is dangerous.

As Malcolm Gladwell put it:

“It takes ten thousand hours to truly master anything. Time spent leads to experience; experience leads to proficiency; and the more proficient you are, the more valuable you’ll be.”

Getting on a boat—whether as skipper or crew—without using every available resource is folly.

A young friend recently asked me to serve as a reference when he signed on as crew for a late-season Annapolis-to-Caribbean passage. After answering the skipper’s questions about my friend, I asked what weather routing support he planned to use.

He told me—proudly—that he’d been in the Navy, had seen plenty of weather files, and didn’t need a router.

That worried me.

I cautioned my friend. Sure enough, they only made it to the mouth of the Chesapeake before turning back—the front they were trying to outrun arrived early. Could they have avoided this if they’d had professional support? Who knows, but my money is on the professional for good guidance.

Forecasts are far better than they were even a few years ago, but I’ve seen many passages where GRIBs painted one picture, only for reality to deliver something very different a few days later.

Conditions change.

One thing doesn’t.

Thy sea is so great, and my boat is so small.

No kidding.

It might be smooth sailing.

But it might not.

Sailor, take warning.

Well said Bob. I have long said that there are no atheists in foxholes, and none on the sea in a storm…